Foreign aid measurement is complicated â what exactly counts as Official Development Assistance, what doesnât, and how much is actually spent abroad?

In 2003, over 1.5 million people worldwide lost their lives to HIV/AIDS. That same year, the United States launched the Presidentâs Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), a program to combat the epidemic. Twenty years later, more than 20 million individuals were receiving life-saving antiretroviral therapy (ART) through PEPFAR.

This is just one example of the benefits that effective foreign aid programs can bring. To understand foreign aid â and to make it work better â we need to understand its key definitions and how it is measured.

The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) sets the standard for measuring and reporting foreign aid. This article presents an overview of how the OECD measures and standardizes foreign aid, explores some surprising components counted as aid in this framework, and discusses the areas where measurement practices occasionally diverge between countries.

Let’s start with one simple number: £223. This is how much foreign aid the United Kingdom gave per UK resident in 2023.1 The chart below shows that this figure represents less than 0.6% of the average income of people in the United Kingdom, measured as Gross National Income (GNI) per capita. 2

Whatâs included in that £223? What categories does the OECD use to break down that £223? And how much of this money is actually spent abroad?

The technical term that researchers use for foreign aid is “Official Development Assistance” (ODA). For money to be counted as ODA by the OECD, it must be administered âwith the promotion of economic development and welfare of developing countries as its main objectiveâ.3

The major donor countries are the so-called âDAC countriesâ, comprising 31 individual countries plus the European Union as an institution. DAC stands for Development Assistance Committee; this group of countries was responsible for 94% of ODA funds in the world in 2022.

A few non-DAC countries, such as Turkey, Saudi Arabia, and Qatar, also voluntarily report statistics on their development finance to the OECD. To keep things simple, weâll refer to all reporting countries together as âdonor countriesâ in this article.

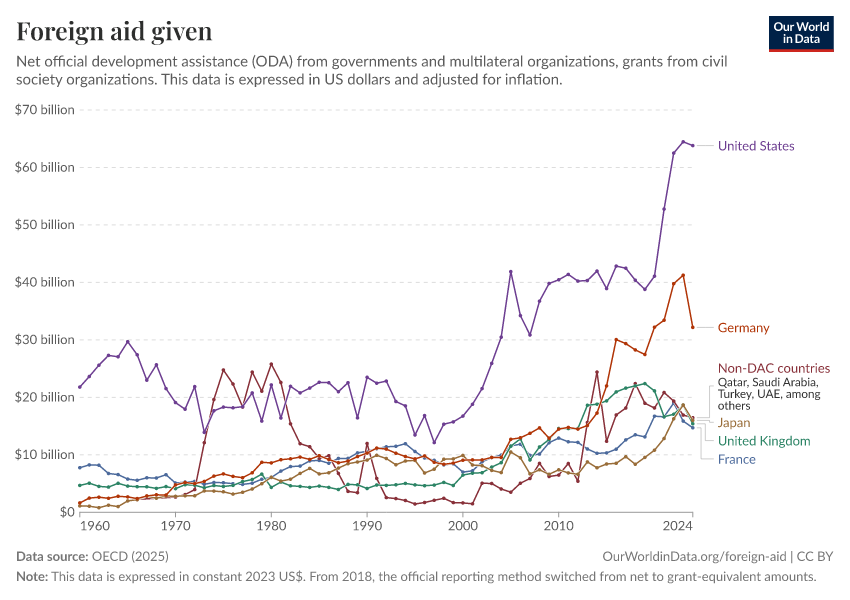

The chart here shows foreign aid from various donor countries, measured in US dollars (adjusted for inflation). While the total amount of aid has increased, DAC countries now contribute a smaller share of their national income to foreign aid than in 1960.

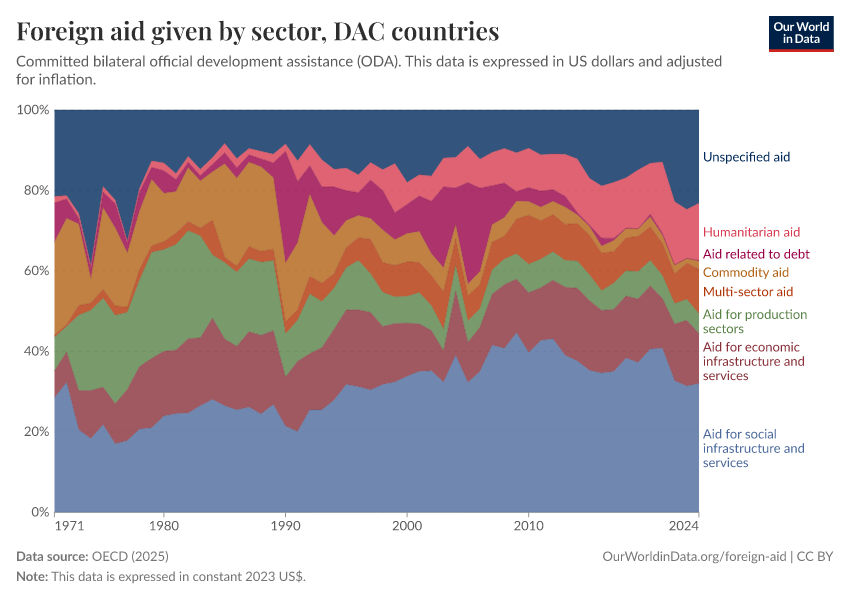

The OECD’s standardized reporting framework helps us understand not only how much aid countries provide but also how that money is used. The chart below shows how donor countries allocate their aid budgets across different sectors, such as social infrastructure, economic infrastructure, production sectors, and humanitarian assistance.

Thanks to these consistent reporting standards, we see clear patterns. For example, DAC countries, on the whole, have allocated approximately a third of their aid budgets to social infrastructure and services since 2000. This category focuses on developing the human resource potential of developing countries and includes areas like education, healthcare, and access to clean water and sanitation.

Still, many questions come up when looking at foreign aid figures closely. Are donor countries giving money away or making loans at reduced interest rates? Are they helping countries develop over decades, or are they responding with help against particular disasters or crises? Does military aid count toward ODA? And â perhaps in conflict with the term foreign aid â how much of this money actually crosses borders and how much is spent within the donor countries?

Grants or grant-equivalents of concessional loans?

Most aid comes as grants; that is, money given to countries and organizations with specific rules about how it can be spent. This is true for all donor countries. In 2022, over 90% of aid from DAC countries worked this way. Most of these grants are a form of bilateral aid, given directly to other countries, rather than multilateral aid, going to multilateral organizations.4

Usually, giving grants means providing things people in lower-income countries need. An example is the aid provided via Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, which has vaccinated hundreds of millions of children against diseases and has been estimated to save 1.5 million lives.But sometimes, donor countries make cheap (âconcessionalâ) loans instead of giving grants. Suppose a poor country normally pays 10% interest but gets a loan at 5%. In that case, the money they save by paying a lower interest rate is counted as aid.5

There are some challenges associated with this method. The first challenge comes in calculating how much the concessional loans are worth. Some experts argue current methods make aid look bigger than it is and that they encourage lending to middle-income countries at near-market rates rather than focusing on low-income countries or providing genuinely favorable loans.6

Secondly, loans to the poorest countries must be more generous than loans to middle-income countries for it to count as aid.7 This may sound sensible â countries may want to help the poorest most â but this rule makes it less likely for the poorest countries to receive aid. If you’re a rich country thinking about making a loan, you might avoid the poorest countries because the loan has to be so generous to count as aid.8

The OECD reporting standards on concessional loans are subject to methodological debates and criticism. However, concessional loans represent only a small fraction of most donor countries’ aid portfolios. In the decade leading up to 2023, concessional loans accounted for merely 7% of donor countries’ total aid disbursements. This means these methodological questions only apply to a relatively small part of the total ODA.

Aid for longer-term development or emergency help?

Foreign aid mostly funds long-term development, but it also provides emergency aid when disasters occur or wars break out. This is often referred to as âhumanitarian aidâ.In 2023, humanitarian aid represented 12% of rich countries’ aid budgets. This includes humanitarian aid for Ukraine, Gaza, and the West Bank.9

Meanwhile, the 2024 Global Humanitarian Overview reports a $36 billion gap between needs and actual funding. If total aid budgets were larger, donors could address humanitarian crises without compromising funding for other projects, such as clean water infrastructure and vaccines.

Countries or private donors?

Most aid comes from government budgets, whether delivered directly or through multilateral organizations. Contributions from private donors, such as the Gates Foundation and the LEGO Foundation, do not count as ODA. These are called âphilanthropic contributionsâ. While not all foundations report their contributions as philanthropic contributions, many of the largest ones do.

In 2022, aid from private donors in the OECD was more than 20 times smaller than government-funded ODA. This means that voters in rich democracies play a crucial role in determining how much aid donor countries spend, as citizens influence policy and taxpayers want their money to be used effectively. They hold agency through the governments they elect and the priorities they demand from them.

Cross-border donations from individuals or money sent back home by migrants donât count as ODA.10

One of the most common questions weâre asked is whether military aid is included in ODA statistics. The answer is no. This ensures consistency across all donor countries, as none can classify their military assistance as official development aid.

This distinction makes a big difference during periods of conflict. Take, for example, US support for Ukraine during the war with Russia. From the Russian attack in February 2022 to January 2025, the US provided about $23 billion per year in military aid to Ukraine.

For context, the US spent $64 billion on foreign aid in 2023, but none of the military assistance is included in these figures.

There’s one exception: countries can count 15% of what they spend on âpeacekeepingâ as foreign aid.11 This works differently because itâs possible to identify how much funding in peacekeeping is going toward developmental objectives, and the money goes through the UN rather than directly to other countries. The UN framework helps avoid some of the contentious problems you get with countries giving military aid directly to each other.

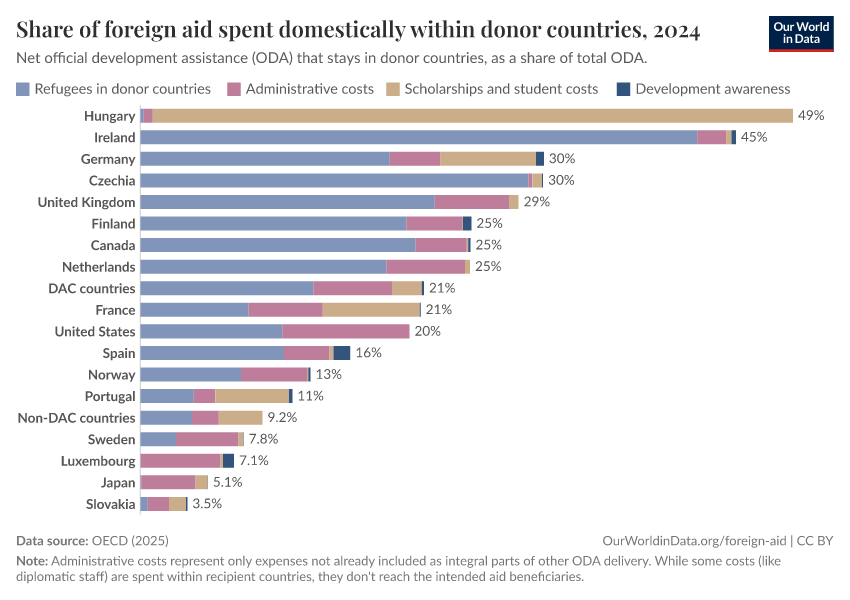

Something that surprises people is that donor countries can count some money they spend domestically as foreign aid. In this article, we call this âaid money spent at homeâ. The OECD reporting framework allows us to see how this practice changes over time and differs across nations. The chart below shows aid money spent at home for all donor countries, broken down by category.

The biggest in-donor cost in 2023 is refugee support. According to the OECD framework, countries can count what they spend on housing, feeding, and administrating refugees for their first twelve months. Including refugee costs might seem odd at first, but there’s a logic: countries spend significant money hosting refugees, and while this doesn’t directly benefit their home countries, it does address the urgent humanitarian needs of foreign citizens whoâve been forcibly displaced.

Another element that may be surprising is student scholarships â these can count as aid when they align with the host country’s development plans.12 For most countries, this contribution is very small. But there are a few exceptions. Hungary is the most extreme case: it uses 41% of its aid budget for foreign students. In addition to refugee support and scholarships, aid money spent domestically includes funding for development awareness programs and administrative costs not already incorporated into specific aid initiatives.

Let’s now look at how individual donor countries differ in their domestic spending of foreign aid budgets. The chart below shows how much foreign aid was spent in DAC countries in 2023, broken down by category.

The arrival of Ukrainian refugees has reshaped aid spending patterns. Thirteen donor countries now spend 20% or more of their aid budget at home â in Ireland, it’s 55%. The UK spends less domestically: 33% of its aid budget, or £74 out of £223 per citizen, mostly on refugee support. These numbers may drop soon. By 2024, most Ukrainian refugees will have been in their host countries for more than a year. After that first year, their support no longer counts as foreign aid.

While a few countries allocate large portions of aid domestically, the broader reality is that most donor nations channel over three-quarters of their aid budgets overseas. We examine the implications and trends of aid money spent at home in greater detail in another article:

How much foreign aid is spent domestically rather than overseas?

In many countries, a significant share of aid is spent domestically on hosting refugees, offering student scholarships, and administrative costs.

There are limitations to measuring foreign aid with Official Development Assistance.

Right now, only rich countries and a few others report it, following rules they set themselves through the OECD.13 Given that rich OECD countries give the most, this covers most aid. However, it leaves out important donors like China, the worldâs largest economy â when accounting for differences in living costs.

A few years ago, researchers at the Center for Global Development proposed a new solution: a measure called Finance for International Development (FID). FID allows us to compare traditional donors, like the US, with newer ones that donât report ODA, such as China.

FID also addresses some of ODAâs most debated aspects â for example, it excludes money spent on refugees in donor countries.14 The available data only extends up to 2019, but at that time, China ranked among the top 10 donors, contributing about one-fifth of what the US did. This measure helps us understand how China’s aid compares to others.

However, ODA is just one type of money that flows from governments in one country to people in others. There’s another category called “Other Official Flows” â the OECD uses this term for financial flows that donât fully count as ODA15, such as commercially motivated grants to build ports using the donor country’s contractors or concessional loans that arenât generous enough to count as aid.

This distinction matters. Between 2014 and 2021, China gave out huge loans through its Belt and Road Initiative. The chart below shows data from AidData comparing ODA and OOF from China and the G7 countries during this period. While their estimate of China’s ODA was much smaller than US aid, its total spending â including these other flows â was more than double. These loans are much less generous than ODA16, but looking only at aid numbers may not capture this bigger picture of how governments fund projects in other countries.

Overall, foreign aid is measured in a way that enables reliable analysis of aid flows. While we’ve highlighted some reporting challenges and variations in this article, these represent exceptions affecting a small portion of total aid.

Most ODA reporting follows consistent standards, providing a solid foundation for meaningful analysis. But understanding the differences and controversies is needed to interpret aid data accurately.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to Euan Ritchie, Ammar Malik, Harsh Desai, Charles Kenny, Hannah Ritchie, Max Roser, Edouard Mathieu, Bastian Herre, and Saloni Dattani for their insights, feedback and comments on this article.

Continue reading on Our World in Data

Many of us can save a childâs life, if we rely on the best data

There are many ways to improve the world, but their cost-effectiveness varies immensely. You can achieve a lot more if you rely on the best data on where to donate.

For many of us, it doesnât cost much to improve someoneâs life, and we can do much more of it

Most countries spend less than 1% of their national income on foreign aid; even small increases could make a big difference.

How much foreign aid is spent domestically rather than overseas?

In many countries, a significant share of aid is spent domestically on hosting refugees, offering student scholarships, and administrative costs.

Cite this work

Our articles and data visualizations rely on work from many different people and organizations. When citing this article, please also cite the underlying data sources. This article can be cited as:

Simon van Teutem and Pablo Arriagada (2025) - âWhat is foreign aid? How âOfficial Development Assistanceâ is measuredâ Published online at OurWorldinData.org. Retrieved from: ' [Online Resource]BibTeX citation

@article{owid-what-is-foreign-aid,

author = {Simon van Teutem and Pablo Arriagada},

title = {What is foreign aid? How âOfficial Development Assistanceâ is measured},

journal = {Our World in Data},

year = {2025},

note = {

}Reuse this work freely

All visualizations, data, and code produced by Our World in Data are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license. You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

The data produced by third parties and made available by Our World in Data is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

All of our charts can be embedded in any site.

#foreign #aid #âOfficial #Development #Assistanceâ #measured