Measles once killed millions every year. Vaccines changed this, preventing disease, long-term immune damage, and deadly outbreaks.

Measles used to be an extremely common disease. Just sixty years ago, over 90% of children would have been infected by it, and of those who developed symptoms, around a quarter would be hospitalized.1

The United States alone had around three to four million cases annually, leading to tens of thousands of hospitalizations and hundreds of deaths each year.2

However, in 1963, John Enders developed the first effective measles vaccine. Vaccination efforts ramped up rapidly in richer countries, and in the 1970s and 1980s, they were scaled up worldwide.

In just the last fifty years, it’s estimated that measles vaccinations have prevented over ninety million deaths worldwide. Two to three million people would die from measles every year without them.3 This means these vaccines are likely the most life-saving ones currently in use, as you can see in the chart.4

In this article, I explain how measles vaccines were developed and their impact on saving lives.

John Enders and his colleagues developed the first measles vaccine. Enders had previously played a key role in research for the development of polio vaccines5 and in 1954, his team turned its attention to measles.

They collected samples from throat swabs and blood from infected school children during an outbreak. The researchers successfully isolated the measles virus from one sample, naming it the “Edmonston strain” after the young boy it came from.6

The next challenge was weakening or “attenuating” the virus so it could trigger immunity without causing disease. Enders and his colleagues experimented with growing the virus in human kidney cells and then in fertilized chicken eggs, forcing it to adapt to different environments. By repeating this process many times, the virus lost its ability to cause severe disease in humans.7

The first human trials in 1960 were successful: school children given the vaccine developed strong immunity and were protected against the virus. However, the vaccine still caused fever and rash in many children. To reduce these side effects, doctors gave children “measles immune globulin” alongside the vaccine to blunt its impact.7

Maurice Hilleman, a microbiologist who developed over 40 vaccines in his lifetime, improved the measles vaccine. In the 1960s, he further weakened the measles virus by growing it in chick embryo cells at lower temperatures, creating an even safer version. It was licensed in 1968 and became the standard measles vaccine. A few years later, in 1971, he developed the measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) combination.8

The impact of measles vaccination was rapid and substantial. Analysis of over a hundred studies shows that the vaccines reduce the chances of developing measles twenty-fold.9

You can see the impact of vaccination in the United States in the heatmap below. Each row is one state, and the colors represent the number of reported cases over time. In the first half of the 20th century, measles rates were high, and the years are shown in dark blue, but the number of cases rapidly dropped due to vaccination.

Other factors have also played a role in the reduction in measles deaths. In the US, deaths had already been falling in the decades before — probably due to better treatment for the secondary infectious diseases that people with measles become vulnerable to, improved sanitation and hygiene that limited the spread of those infections, and better childhood nutrition, which lowered the risk of severe illness.10

However, these improvements were not effective in reducing measles cases. The measles virus is airborne, so improvements in hygiene, such as clean water or better sewage systems, do not reduce its spread. Since measles is so contagious, nearly every child still got measles before vaccines were available11, and the number of cases only began to decline after the vaccines arrived.

Yet this doesn’t mean these cases were mild: before vaccines were available, there were still around 50,000 hospitalizations and hundreds of deaths in just the United States each year.2

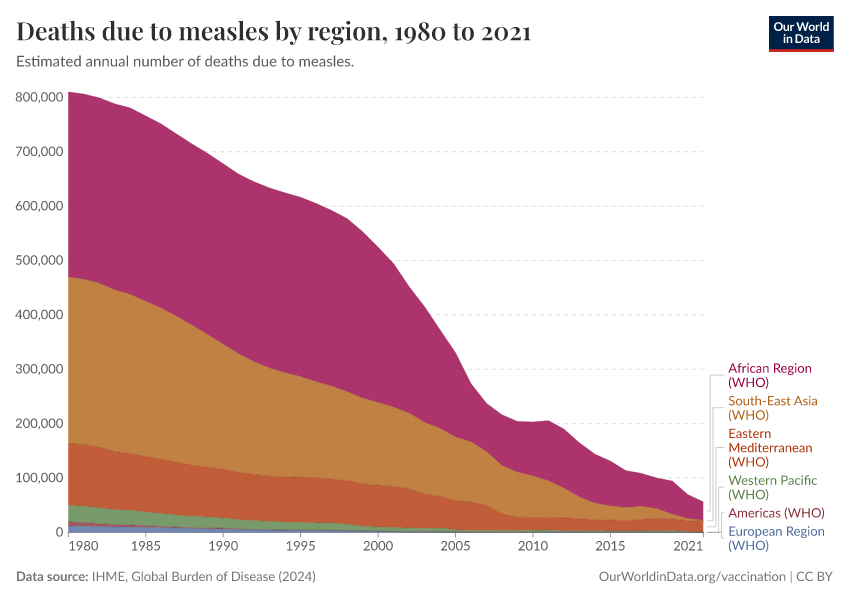

In contrast, measles deaths continued to be common in poorer countries until vaccines became widely available. In the chart below, you can see that hundreds of thousands of people died from measles annually in Africa and South-East Asia between the 1980s and 2000s.

That’s because, in low- and middle-income countries, the case fatality rate from measles has been much higher than in richer countries. It’s estimated that in the 1980s, 5 to 10% of children with the disease then died from it. This would have been particularly severe when widespread measles outbreaks infected most children in the population.12

The number of measles deaths dropped dramatically in the 2000s, particularly in Africa, as vaccination efforts scaled up, as we’ll see in the following section.

The global rollout of measles vaccines has been one of history’s most successful public health efforts. Each year, they save millions of lives.

This is especially true in low-income countries where children face the highest risk of dying from measles because of poorer overall health, nutrition, and living standards.10

This chart shows how far the world has come. It shows the share of one-year-olds who have received their first dose of the measles vaccine.

In the 1980s, coverage was very low in many parts of the world, especially in Africa, Southeast Asia, and the Eastern Mediterranean. In some countries, like Yemen, only 2% of children received vaccines; in Spain, only 8%.

But since then, vaccination rates have increased rapidly.

One reason is the scale-up of the Expanded Programme on Immunization by the World Health Assembly from the 1970s, which aimed to vaccinate children against the deadliest infectious diseases, including measles. Vaccination efforts reached more than 90 million children — or 60% of all infants — by the early 2000s.

But millions of children were still left behind, particularly in poorer countries. In response, the Gavi Vaccine Alliance was established in 2000 to close these gaps and ensure that life-saving vaccines reached the most vulnerable children.

Now, over a hundred million infants receive vaccinations for measles, which is over 80% of them.

These efforts have transformed global health, dramatically reducing child mortality.

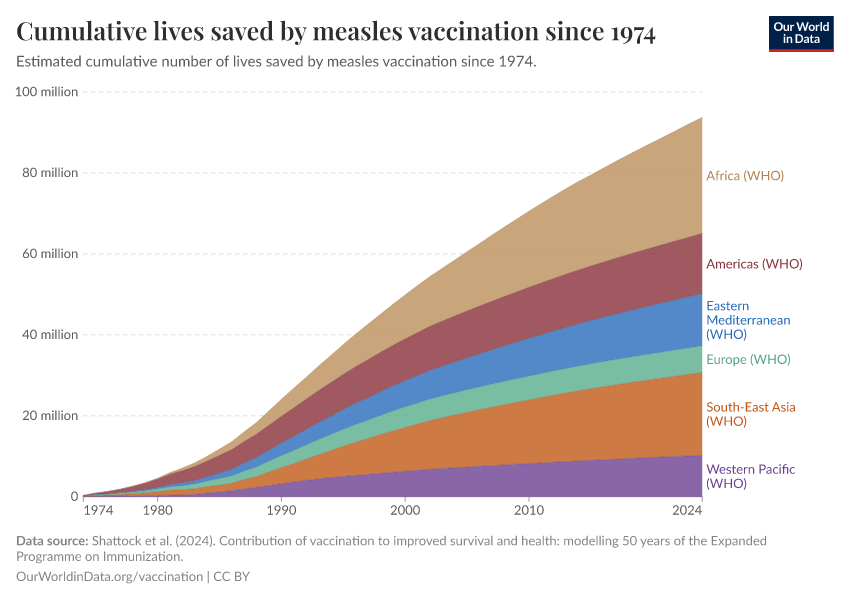

This next chart shows estimates of the cumulative number of lives saved by measles vaccinations over time.13

Fifty years since the start of measles vaccination programs, we can see that their impact has been substantial: researchers estimate that 94 million lives have been saved from measles vaccines. That means, on average, nearly two million measles deaths prevented every year.13

The impact has been greatest in Africa, with 29 million lives saved, and Southeast Asia, with 20 million lives saved. These are regions where measles was a leading cause of death in children until recently.

This means measles vaccines rank as the most life-saving childhood vaccines currently in use.4

Measles was once an unavoidable disease, infecting nearly every child and causing millions of deaths each year. This was not because of poor hygiene or healthcare, but because of how contagious measles is. Without immunity, each infected person would typically pass it to more than a dozen others14, making sanitation and hygiene measures alone insufficient to control its spread.

The breakthrough came when researchers isolated and weakened the virus, creating a safe and effective vaccine. Over the following decades, measles vaccination was scaled up globally, reaching hundreds of millions of children and preventing an estimated 90 million deaths in the last fifty years — more than any other childhood vaccine used today.

Measles vaccination does more than prevent the disease. It preserves a child’s broader immunity and protects those most at risk, including infants, pregnant women, and people with weakened immune systems from health conditions or undergoing cancer treatments.

It also prevents the virus from spreading. When most people are immune, the virus runs into dead ends. Chains of transmission are broken before they can grow. As a result, outbreaks have become smaller, easier to contain, and increasingly rare. But keeping it this way requires high vaccination rates: the best way to stop a measles outbreak is to prevent it from ever starting.

Continue reading on Our World in Data

How effective and safe are measles vaccines?

Data from large meta-analyses show that measles vaccination is highly effective and safe, giving a 95% reduction in the risk of measles.

Vaccines have saved 150 million children over the last 50 years

Every ten seconds, one child is saved by a vaccine against a fatal disease.

Our history is a battle against the microbes: we lost terribly before science, public health, and vaccines allowed us to protect ourselves

For most of our history, we were losing terribly against the microbes. Only recently did we turn the battle in our favor. Vaccines were a major breakthrough.

Cite this work

Our articles and data visualizations rely on work from many different people and organizations. When citing this article, please also cite the underlying data sources. This article can be cited as:

Saloni Dattani and Fiona Spooner (2025) - “Measles vaccines save millions of lives each year” Published online at OurWorldinData.org. Retrieved from: ' [Online Resource]BibTeX citation

@article{owid-measles-vaccines-save-lives,

author = {Saloni Dattani and Fiona Spooner},

title = {Measles vaccines save millions of lives each year},

journal = {Our World in Data},

year = {2025},

note = {

}Reuse this work freely

All visualizations, data, and code produced by Our World in Data are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license. You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

The data produced by third parties and made available by Our World in Data is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

All of our charts can be embedded in any site.

#Measles #vaccines #save #millions #lives #year